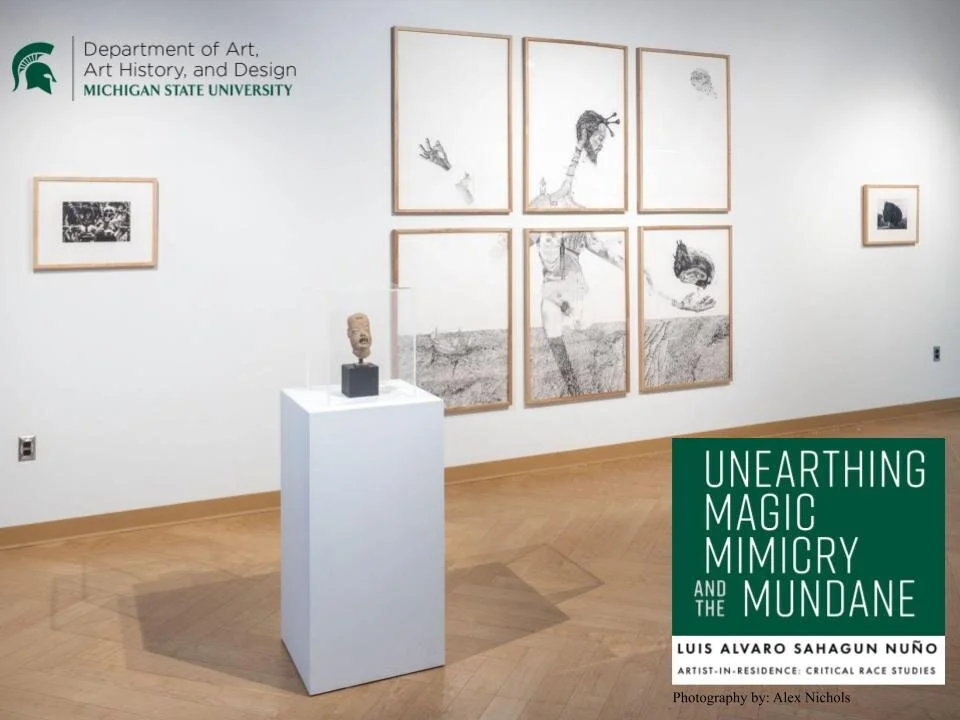

Unearthing: Magic, Mimicry, and the Mundane

PDF of exhibition with catalog essay

SIGNING THE CROSS: on the many hand signals of divination and survival in the work of Luis Sahagun.

Exhibition Essay by Raquel Gutierrez

The gestural histories of the Mexican quixotic vibrates in the art of Luis A. Sahagun and does so through the most salient of appendages—the hand. The sacred figuration of the hand is one of the oldest mystical symbols in the world. Depictions of the open right hand, for example, is most notable in La Mano Poderosa (The All-Powerful Hand), a devotional image of the child Christ flanked by his parents and grandparents on each finger, the holy family floating above the open wound of the stigmata. There’s also the palm-shaped image of the hamsa and the eye it holds in its center has long been believed of its powers against evil, as well as a symbol of good fortune. For Sahagun the hand is a repository of energy that becomes activated through recognizable patterns of embodied communication. But these are also the hands that honor the labors of the working class from which he proudly emerges.

At a 2019 artist talk at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum and in connection to critical race studies with MSU (shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic forced a series of national shutdowns) Sahagun spoke of the conundrum the Mexican philosopher Octavio Paz had first articulated in his seminal work The Labyrinth of Solitude of not belonging in the US and not belonging in Mexico. That in the place of said belonging emerges a new culture that Paz calls a cultural suicide. While Paz may think of this unbelonging as a dead end Sahagun thinks of it as a cultural reclamation—built on negation and need. I can be whatever I want out of necessity he tells the audience. He punctuated this point with a performance. He raised both hands in a prayer gesture with pointer and pinkies touching in front of his face. With his fingers still clasped Sahagun brought his hands over his head, covered in the hood of his sweatshirt emblazoned with the word Scholar, as if mimicking a rooster’s red comb, twisting his fingers into Cs and Hs, speaking a language resonant of the Chicago Heights neighborhood the artist called home since arriving there from Mexico with his mother at the age of 4. Speaking it with his whole chest.

In that moment Sahagun called in the mode of identification known as ‘stacking,’ a series of hand gestures that signal the gang or neighborhood with which someone is affiliated. It is with said hands that Sahagun recenters indigenous cosmological worldviews that provides a sense of the visionary and unpredictable in the visual historical index that underpins Unearthing: Magic, Mimicry, and the Mundane.

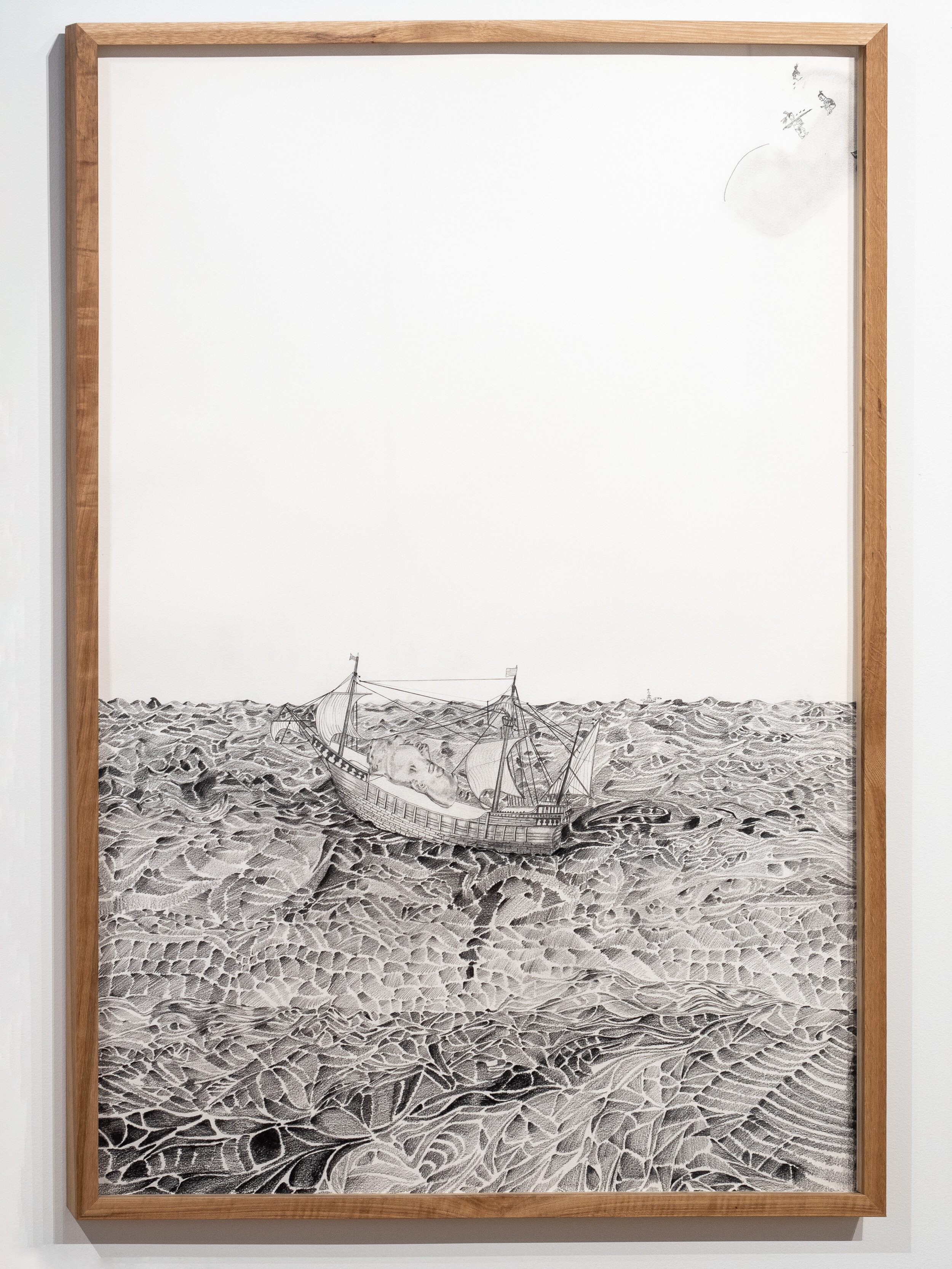

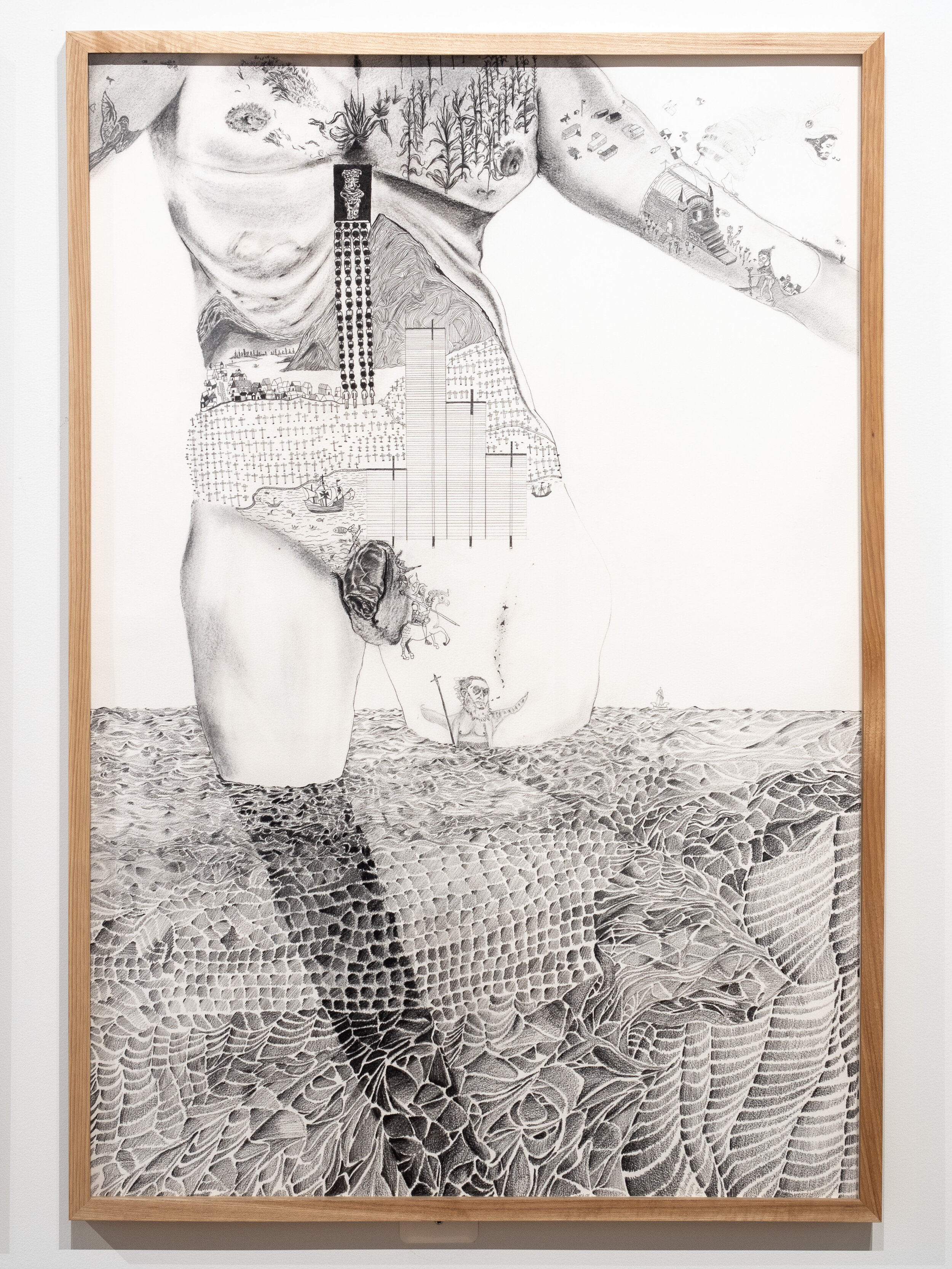

As you walk through the MSU Union Art Gallery you’ll find Sahagun’s surreal and gloriously rendered 6-paneled graphite and charcoal drawing Magia Madre (Mother Magic) as the exhibition’s anchoring work. This is the vehicle in which Sahagun takes us through the citational wonderland of the Broad Museum’s collection of Mexican masters and their works, revealing the shared connection facilitated by the magical qualities of the most mundane of extremities—the hand, a tool for conjuring. The hand functions as the conceptual constellation connecting Sahagun to the transformational power staged in each of the works present by both the known artists (Rufino Tamayo, Flor Garduño and Graciela Iturbide) alongside the unknown artists of ancient Pre-Columbian civilizations. Tamayo’s Observador de Pájaros (Bird Watcher). Sahagun’s engages in a call-and-response to each of the works—whether it is through the matrilineal allusions in Iturbide’s Manos Poderosas, Juchitán or the elongated palms, necks, hair locks, and torsos in both his and Tamayo’s Observador de Pájaros (Bird Watcher) or the sweeping movement of the tear-drop shaped tree echoed in the woman figure holding one arm out to her side. Sahagun’s figures hover in various elemental states—in the ether just above an open palm, in the still, mosaic waters that hold the artist’s protagonized self in view; cornfields traversing the wound of the border across his body the terrestrial site of conquest, growth and rediscovery.

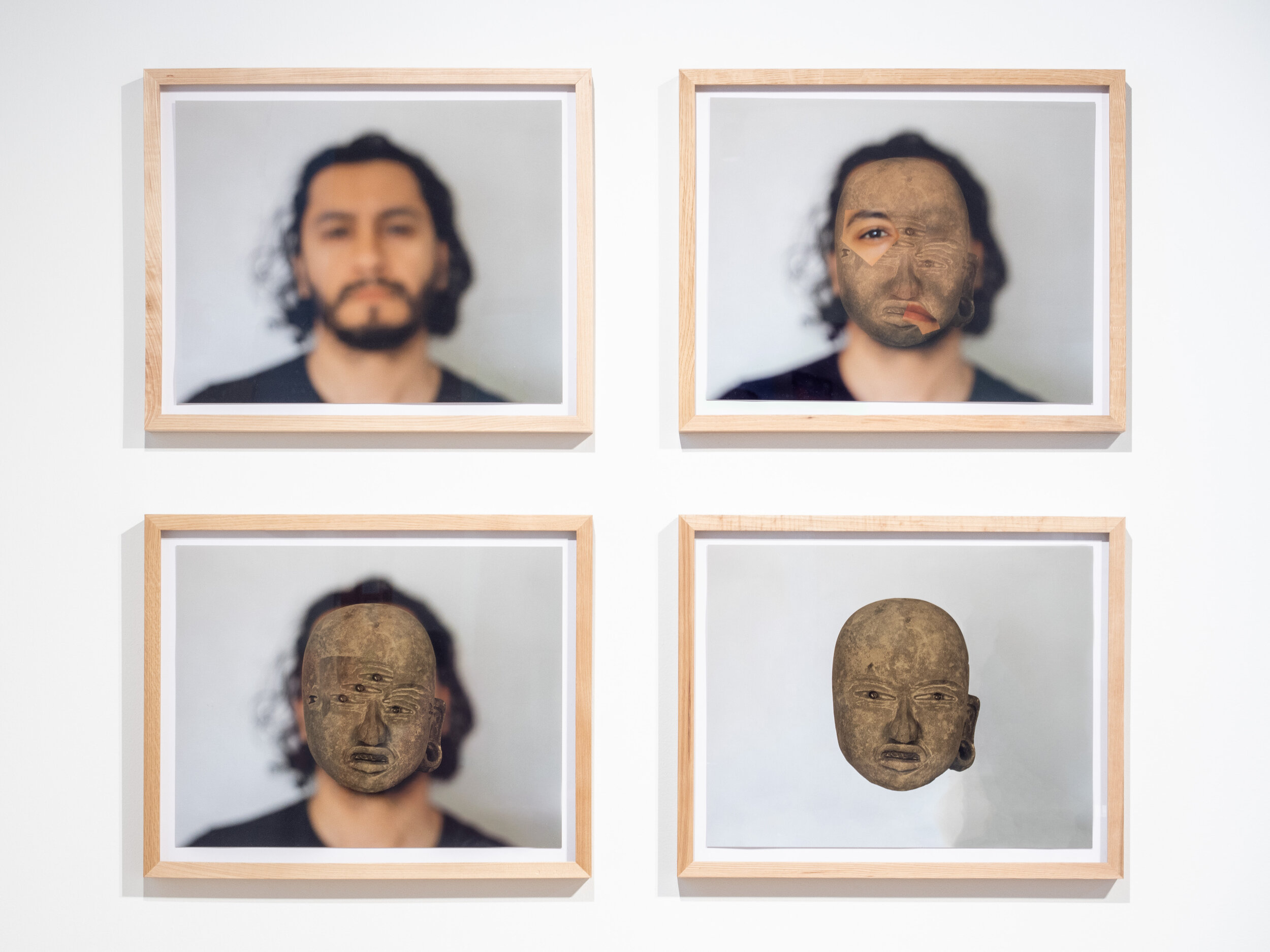

It is here where Sahagun reminds us that the crossing of two cultures often happens under the sign of the cross. The right hand is clawed into the self blessing gesture (a rooster shaped shadow puppet) in diagonal opposition to the groin section where scores of crosses compose a graveyard of unnamed ancestors stacked atop one another. Forgotten as if to make way for a new people in a new world. It is that historical atrocity that for Sahagun serves as a reminder of the ways anonymity confines the ancient objects of the heads and stone figurines to the space of the museum instead of the communal space. Sahagun’s engagement with these objects serves as a spiritual reclamation and healing from that rupture.

These are the objects that facilitate Sahagun’s state of calling in and engaging in the seven-stage sense-centered critical knowledge making process that borderlands philosopher Gloria Anzaldúa has articulated in her posthumous book of essays Light In The Dark/En Lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality as conocimiento. Conocimiento is a structure of healing that resembles closely the seven chakras of the “energetic dreambody,” that incite the senses towards a radical self-awareness, one capable of causing internal shifts and external changes having to do with the shadow self, a spiritual reckoning with the unwanted aspects of the self.

It is here that we as spectators, receivers, and witnesses to the work are guided through the difficult grief-space of loss and healing alongside the vexed relationship between viewer and institution. What is recognition to the shadowed self? What is the museum to the culturally suicidal? A shape-shifter in search of a stable context? An object in search of its maker? An author crafting meaning out of necessity. As Sahagun reminds us, he comes from “a place formally or traditionally referred to as nothing, but that nothing has always been [his] everything.”

raquel gutiérrez is an essayist, arts critic/writer, and poet. Born and raised in Los Angeles they currently live in Tucson, Arizona where they just completed two MFAs in Poetry and Non-Fiction from the University of Arizona. Raquel is a 2017 recipient of the Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant. Raquel also runs the tiny press, Econo Textual Objects (est. 2014), which publishes intimate works by QTPOC poets. Their poetry and essays have appeared or are forthcoming in Los Angeles Review of Books, The New Inquiry, FENCE, Huizache, The Georgia Review, The Texas Review and Hayden’s Ferry Review. Raquel’s first book of prose, Brown Neon, will be published by Coffee House Press in the Spring of 2021. And Raquel's first book of poetry, Southwest Reconstruction, will be published by Noemi Press in 2022.

LUIS ALVARO SAHAGUN NUNO VISITING ARTIST-IN-RESIDENCE: CRITICAL RACE STUDIES LECTURE.